On desire,

writing

Zara

and thwarted

dissolution

Sigglekow

On desire, writing and thwarted dissolution

Zara Sigglekow

To dissolve is to become infinite, and to desire offers a possibility of this dissipation. In desiring, there is an ever-present conflict between maintaining integrity and falling into the thing – of subjective projection onto the thing, and letting it hold its own. More generally, this might be described as feeling complete and in control, versus getting lost in something (people, bodies, art works).

Writing about art is an act of desire that flits between wholeness and dissolution. It is in the latent potential of this space that writing rests, a symbiosis of author and artwork.

✻

Maggie Nelson looks to Joseph Cornell, who conceives of desire as a ‘sharpness’, ‘a tear in the static of everyday life’1. Someone else I read, I forget who, wrote that falling in love and intellectual revelation create the same burst of energy. It’s this jolt of desire that compels us. This is why we might write.

✻

The Greek word eros, another name for desire, denotes ‘want,’ ‘lack’ or ‘desire for that which is missing’2. Lauren Berlant writes

desire describes a state of attachment to something or someone, and the cloud of possibility that is generated by the gap between an object’s specificity and the needs and promises projected onto it.3

The artwork exists as an entity of ideas, aesthetics and positions. To write about it is to seek to understand these specificities, to get to know it with freshly scrubbed eyes. I want to see the work anew through language when I write. But desire only holds in the gap: the space between the self and the object. In this void writing rests, hovering in a bundle of syntax.

Before we get lost in something we come to something. One objective of writing about art is to describe, to record, which involves repeating the work back to the reader in a failed facsimile: the words never quite match. But the build-up of description is an act of desire, as I try to find the correct language, getting close and casting a net that draws in an intimate haul. Adopting language to match the thing tightens the net of intimacy in an attempt that is both mimetic, and a desire to merge. In this, the surface of writing is desire-in-action as words jangle together, moving forward – sometimes luminescent, and sometimes flat – toward an intimate knowing of the art work. An attempt at dissolution, a melting with words.

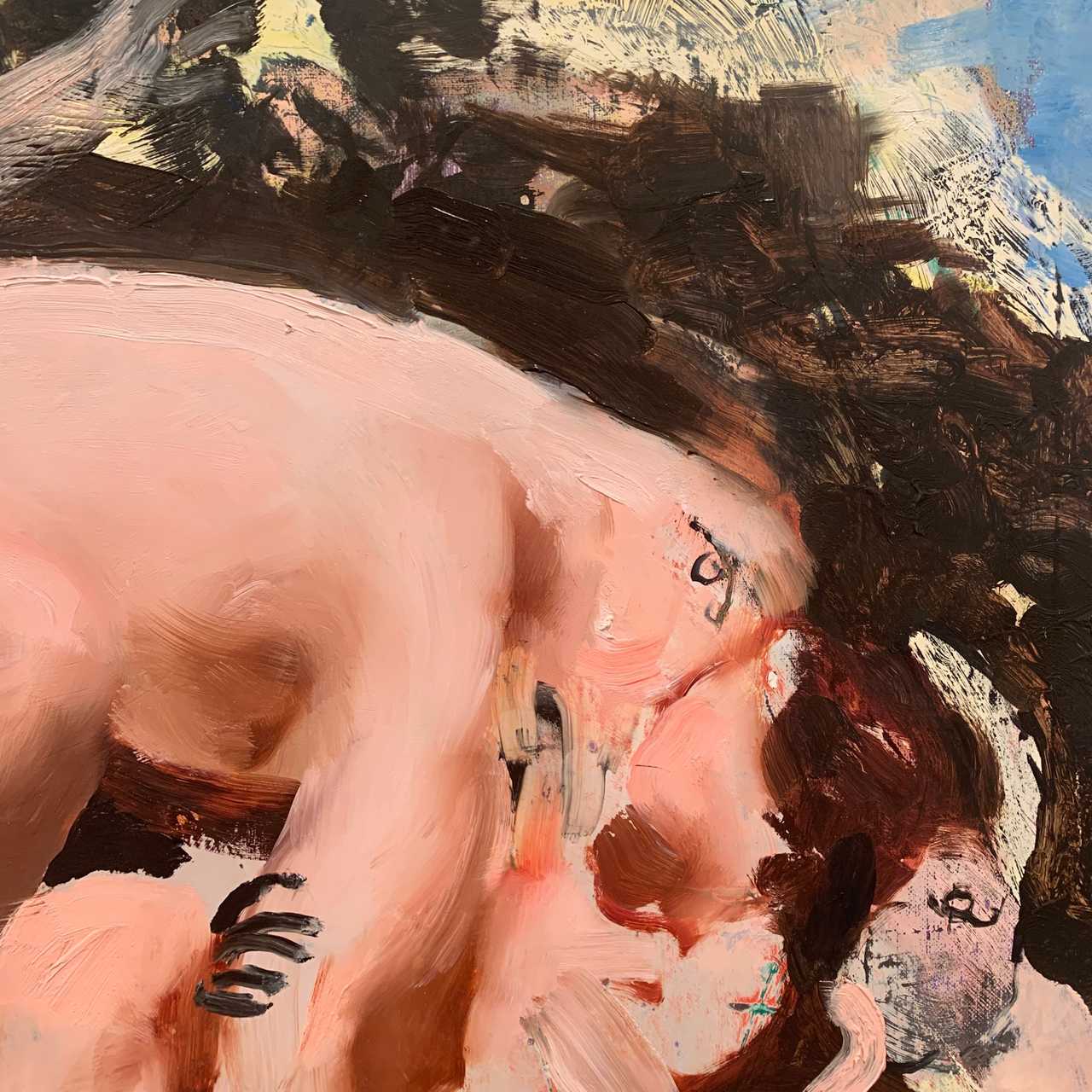

Both bodies are made up of swishing brushstrokes in shades of skin and brown for shadows. Five black fingers grasp their partner's upper arm, like five twigs, their scratchiness incongruent to the rest of the mass. It’s a grasp out of a void of desire. The fingers are particular – the small details that you unexpectedly notice on a person, like an uneven toenail. All this amidst collapsing edges, collapsing boundaries. Wellman speaks of desire as an engine and a ‘self in process’ that pushes a space for identity to form.

✻

Yet another purpose of writing about art is meaning-making and this involves projection such as veiling the work with art historical context or the lens of theory. Something like Berlant’s ‘needs and promises’ that we project onto the thing. This part of desire, of hauling ourselves around and onto what we encounter, thwarts dissolution. The net we cast with our language is laced with our own meaning in a bid to make the artworks work for us.

✻

These paintings by Harris and Wellman have points of dissolution or skirt around its borders. In Harris’s painting, Mary Magdalene reaches out to touch the abyss where infinity might reside. Writing almost accesses this void but, ultimately, it lies beyond the edges of language. And Wellman's lovers falling into each other in lust – their bodies physically dissolving – perform what cannot be achieved in reality but what I might try to do in writing.

Anne Carson writes that ‘eros is an issue of boundaries’. Gaps are where desire is manifested and fostered, and the ultimate edge is the edge of the body – ‘the boundary of flesh between you and me’, she says: ‘And it is only, suddenly, at the moment when I would dissolve that boundary, I realise I never can.’4

I write and I cannot dissolve, so I move on to the next piece. The next object, the next person, the next thing.

Images:

Brent Harris, Borrowed plumage #3 (noli me tangere) 2007, oil on linen, 244.0 x136.0 cm,

Private Collection, Melbourne. Detail view, Australian Centre for Contemporary Art, Melbourne 2019.

Photograph by Zara Sigglekow

Ambera Wellman, Limbal 2019, oil on linen, 49.0 x 52.0 cm, courtesy of the artist

and Kraupa-Tuskany Zeidler, Berlin. Detail view, Australian Centre for Contemporary Art, Melbourne 2019.

Photograph by Zara Sigglekow

-

Maggie Nelson, Bluets, Penguin Random House, London, 2009, p. 71

↩ -

Anne Carson, Eros the Bittersweet, Princeton University Press, Princeton, 1986, p. 10

↩ -

Lauren Berlant, Desire/Love, punctum books, Brooklyn, 2012, p. 6

↩ -

Anne Carson, Eros the Bittersweet, Princeton University Press, Princeton, 1986, p. 30

↩

Brent Harris’s paintings of a Mary Magdalene figure standing on a hill, her back to us, her hand reaches out to touch a bull’s eye hole. In this case a void, an absence – a metaphor for the body’s inevitable mortality. It’s lifted from a biblical scene, Noli Me Tangere, which Harris says is allegorical of a life situation – “on the death of a friend, you can no longer touch them in the flesh, you touch them in spirit. It’s a question of testing belief,” he says. They are about – existential questioning, touch, the finitude of life and the infinity of death.